How many religious congregations are there in the United States?

There is no official directory for all the congregations in the country, so sociologists of religion have to rely on statistical estimates from surveys and results from the decadal US Religion Census. The numbers of churches in the US are often disputed, and to complicate matters, thousands of new churches open each year while thousands of others close.

Hartford Institute estimates there are roughly 370,000 religious congregations in the United States. This figure is midway between the lower US Religion Census 2020 count of 356,642 religious congregations and the higher estimate of 384,000 by Simon G. Brauer (2017, “How Many Congregations Are There? Updating a Survey-Based Estimate,” in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, Vol. 56, No. 2, pp. 438-448). Within this estimate of 370,000, approximately 332,000 are Protestant and other Christian churches, 23,000 are Catholic and Orthodox churches, and about 15,000 are religious congregations or communities of other faiths.

Want to know more? Check out the US Religion Census.

How big are US churches?

According to the 2023 Faith Communities Today national survey, the average church in the US has a median of 60 regular worship participants. Median church size means the midpoint at which half the churches are smaller and half the churches are larger—rather than the average, which is larger due to the influence of very large churches.

However, while the United States has many very small churches, most attend larger ones. The 2023 Faith Communities Today study estimated that 70% of smaller churches (100 participants or less) draw only 14% of all those in the US who attend worship. However, 70% of churchgoers attend the largest 10% of congregations (over 250 regular participants). These size dynamics and distribution of attendees are identical when combining the congregations of all Christian and other faiths. In many ways, the United States is a nation of small congregations with few people, and a small percentage of large congregations are home to most attendees.

Want to know more? Check out the Faith Communities Today studies.

How many people go to church each Sunday?

For years, Gallup, Inc. identified a consistent 40% of all Americans who said they attended worship on the previous weekend. Sociologists of religion have questioned that figure, saying Americans tend to exaggerate how often they attend. By actually counting the number of people who showed up at a representative sample of churches, two researchers, Kirk Hadaway and Penny Marler, found that only 20.4% of the population attended church each weekend. In a 2024 poll, Gallup’s figures also showed that 21% of Americans claimed to attend weekly. Recent research using cell phone data has indicated that significantly fewer people are likely to be attending every week. Still, the estimate could be between 10% to 20% of Americans who attend weekly. Based on Pew Research Center data, we know that Americans are attending weekly with less frequency than in past decades.

Does that mean frequent churchgoers are less honest? Not necessarily. Instead, misreporting seems tied to people’s perception of themselves as active churchgoers. Americans tend to overrate desirable behavior. That’s why people overestimate the number of times they voted or the number of times they gave money to the poor. So long as people hold the church in great esteem, they will exaggerate their attendance at worship. However, the results of these two studies have other implications. They suggest that inflated church attendance figures have produced a distorted image of religion in America. “If real,” the researchers concluded, “a large attendance gap suggests that many assumptions about the robustness and exceptional nature of religion in America should be modified.”

How many denominational groups are there in the United States?

This is a tough question because it depends on how a denomination is defined. The 2006 Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches listed 217 denominations. However, there may well be other groups that function as denominations but do not regard themselves as such.

The single largest religious group in the United States is the Roman Catholic Church, which had 67 million members in 2005. The Southern Baptist Convention, with 16 million members, was the largest of the Protestant denominations. The United Methodist Church was the second-largest Protestant denomination, with eight million members. In third and fourth spots were the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, known as the Mormon church, with six million members, and the Church of God in Christ, a predominantly black Pentecostal denomination, with 5.5 million members.

However, since the Religious Congregations & Membership 2010 study, we now know that the grouping of nondenominational churches, if taken together, would be the second-largest Protestant group in the country, with over 35,000 independent or nondenominational churches representing more than 12,200,000 adherents. These nondenominational churches are present in every state, and 2,663 out of 3,033 counties in the country, or 88% of the total.

Want to know more? Check out the 2012 Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches. You can also find a listing of denominational websites on our site.

How multiracial are US churches?

Over the last three decades, congregations have become increasing multiracial. Where our 2010 Faith Communities Today study of over 11,000 congregations found the percentage of multiracial congregations (based on the 20% or more minority criteria) had nearly doubled in the past decade to 13.7%, the more recent 2020 Faith Communities Today study shows that 25% of congregations were multiracial.

A late 1990s study by sociologist Michael Emerson showed that “multiracial churches” (where 20% of members were of different racial groups from that congregation’s majority race) accounted for 7-8% of US congregations.

Our 2010 study indicated that the percentage of multiracial congregations is increasing in all faith groupings. In Emerson’s study, 5% of Protestant churches and 15% of Roman Catholic churches were multiracial, while in 2010, 12.5% of Protestant churches and 27% of other Christian churches (Catholic/Orthodox) were multiracial.

Additionally, non-Christian congregations have considerable racial diversity. The 2010 survey found that 35% of congregations in faith traditions such as Baháʼí, Muslim, Sikh, and others were multiracial.

The largest churches in the country also seem to have it easier. Large Catholic churches are significantly multiracial. Likewise, sociologist Scott Thumma found, in the 2005 Megachurches Today study, that megachurches have a multiracial advantage as well. In his study, 35% of megachurches claimed to have 20% or more minorities. What’s more, 56% of megachurches said they were making an intentional effort to become multiracial.

Want to know more? Check out People of the Dream: Multiracial Congregations in the United States (Princeton University Press, 2006) or other books by Michael Emerson. Also, read the Megachurches Today 2005 report.

How many clergymen and women are there in the United States?

The Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches reported 600,000 clergy serving in various denominations in the United States. But that figure included retired clergy; chaplains in hospitals, prisons, and the military; denominational executives; and ordained faculty at divinity schools and seminaries. The 600,000 figure did not include independent churches, not tied to a denomination.

“There’s no way to know how many there are,” said Jackson Carroll, Williams Professor Emeritus of Religion and Society at Duke Divinity School. In addition, Carroll said the figures provided by the denominations in the Yearbook may not be that accurate. Nevertheless, at present, it is the best figure to use.

Want to know more? Read Chapter 3 in Carroll’s God’s Potters: Pastoral Leadership and the Shaping of Congregations (W.B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2006).

What’s the average age of congregational leaders?

In the past few decades, men and women have entered the ministry at older ages. Most had another career before going to seminary, and by the time they settled into the role of minister, they tended to be middle-aged. In a recent study, the median age of senior or solo Protestant pastors was 51. The median age of senior or solo Black pastors was 53. Roman Catholic priests are the oldest; their median age was 56. Associate pastors and those serving in non-church settings tended to be slightly younger. In a 2001 US Bureau of Labor Statistics report, the median age of full-time, graduate-educated ministers was 45. Our more recent research from the Exploring the Pandemic Impact on Congregations Study puts the median age at 59 years.

Want to know more? Read Chapter 3 in Carroll’s God’s Potters: Pastoral Leadership and the Shaping of Congregations (W.B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2006).

Is there a clergy shortage since the pandemic?

Yes and no. One of the chief worries facing seminary students in protestant denominations as they approach graduation is whether or not they will be able to fulfill their calling to the ministry by finding a job that suits their vocational and lifestyle needs.

While the answer to these questions varies for each individual, sociologists approach the questions more broadly by asking, “What is the structure of opportunities in the job market?” In other words, how many people are looking for a job compared to how many jobs are available? How likely is it that job seekers will be matched with the right opportunities?

Current data suggests that as the number of small churches expands and the majority of churchgoers flock to larger megachurches, the structures of opportunities for clergy are shifting. Fewer and fewer clergy will be able to follow a traditional career path of upward professional mobility. As opportunities narrow sharply towards the top, more and more individual clergy cannot move into larger churches.

However, this recent research shows the reasons are not an individual’s failure to fulfill their calling but rather a skewed labor market. This market offers ample opportunities in the smallest churches and increasingly fewer positions in the largest churches.

Today’s clergy market displays four important features:

- There is a surplus of clergy to fill the available positions. If one looks at the number of ordained clergy compared to the number of churches in a denomination, in some cases, there are as many as two clergy per church, with seminary enrollments continuing to climb. This data contradicts the perception that there is a clergy shortage.

- However, there is a high vacancy rate if one looks at the number of clergy serving in churches. A high number of churches are without a full-time pastor. This vacancy rate supports the perception of a clergy shortage. What the perception obscures, however, is that the shortage tends to be located in small churches.

- Most churches in the US are small, with 100 or fewer members.

- Most church attendees go to large churches with 350 or more members.

In other words, the structure of opportunity provides ample jobs for clergy interested in serving small churches but far fewer for those wishing to serve in medium or large churches. Seminary students, most of whom were raised and formed in large churches (as are the majority of the American population), feel called to serve in the kind of churches in which they were raised, but these opportunities are declining.

Many clergy are frustrated at their inability to find what they consider a “better” job in a larger church. Rather than seeing the realities of the job market, they personalize the issue and feel they failed, were discriminated against, consider switching jobs, or contemplate dropping out of the ministry. Looking at the job market this way reconciles two dissonant impressions held by denominational leaders and clergy.

Leaders look at the vacancy rate in the small churches and see a clergy shortage that needs to be addressed by increasing seminary enrollments.

Existing clergy sees a surplus of clergy competing for the same jobs, forcing many to work part-time outside the church, move into non-parish positions, and ultimately begin new careers because they cannot find an adequate position within a church setting.

Both perceptions are correct. The problem is not one of shortages; it’s a problem of balance.

What’s the definition of a megachurch, and how many are there in the United States?

Megachurches are not all alike but share some common features. Sociologist Scott Thumma defines a megachurch as a congregation with at least 2,000 people attending each weekend. These churches tend to have a charismatic senior minister and an active array of social and outreach ministries seven days a week.

As of 2020, there were roughly 1,800 Protestant churches in the United States with a weekly attendance of 2,000 people or more. Likewise, the percentage of Americans attending a megachurch has continued to rise, suggesting people continue to be receptive to this large-scale worship. The average megachurch had a Sunday attendance of 4,092. But not all megachurches are mega. Our surveys found that just 20% of megachurches had 5,000 people in attendance on a given Sunday.

Want to know more? Read a detailed description of megachurches.

Where are megachurches located?

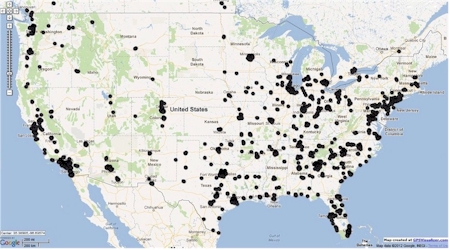

Megachurches have become a religious phenomenon spread across the US. All but two states have congregations with more than 2,000 people in attendance on a Sunday morning. The four states with the greatest concentrations of megachurches were California (14%), Texas (13%), Florida (7%), and Georgia (6%). The following map shows the locations of all the US megachurches in 2012. Each black dot represents a church, with the large black masses indicating multiple churches within an area:

Want to know more? Read about our megachurch research.

How many Muslims are there in the United States?

This is a hotly debated issue with political overtones. There are currently several studies claiming between 1.5 and 6 million Muslims in the United States. The problem is the US Census is prohibited from asking about religious affiliation. Researchers have used different methodologies to compensate for the lack of solid numbers. A 2001 study titled “Mosque in America: A National Portrait” reported 6 million Muslims in the United States. But Tom W. Smith of the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago said those numbers were inflated and that there were 1.9 million Muslims in the United States.

The 2010 Mosque study, The American Mosque 2011, indicates that the number of American mosques has increased by 74% since 2000 and that Islamic houses of worship are ethnically diverse institutions led by officials who advocate positive civic engagement. From 1,209 mosques in 2000 to 2,106 in 2011, New York and California have the largest number, 257 and 246 mosques, respectively.

- The American mosque is a remarkably young institution; more than three-fourths (76%) of all existing mosques were established since 1980.

- The number of mosques in urban areas is decreasing, while the number in suburban areas is increasing. In 2011, 28% of mosques were located in the suburbs, up from 16% in 2000. The number of mosques with large attendance has increased. In 2000, there were only 12% of mosques with attendance of over 500, and in 2011, there were 18% with attendance of over 500 people. More than 2% of American mosques can be classified as megachurches or “megamosques,” which are defined as a congregation with an attendance of 2000 or more people.

- Mosques remain an extremely diverse religious institution. Only a tiny minority of mosques (3%) have just one ethnic group that attends that mosque. South Asians, Arab Americans, and African Americans remain the dominant ethnic groups, but significant numbers of Somalis, West Africans, and Iraqis now worship at mosques nationwide.

- The conversion rate per mosque has remained steady over the past two decades. In 2011, the average number of converts per mosque was 15.3. In 2000, the average was 16.3 converts per mosque.

Want to know more? Read Mosque in America: A National Portrait, which is a survey released in 2001, the 2010 study in three parts, and the 2020 study. For a different perspective, see Estimating the Muslim Population in the United States by Tom W. Smith.

How quickly are Muslim mosques growing in the US?

At an almost unparalleled rate! According to the recent Faith Communities Today (FACT) study, membership in Muslim mosques is increasing at a rapid pace, coming in second only to megachurches in the United States.

Mosques trailed megachurches, 83% of which grew by 10% or more in membership from 1995 to 2000 compared to 60% of masjids, the Arabic term for a Muslim congregation, which grew by 10% or more in that same period. Ten percent or more congregational growth was found in 48% of Latter-day Saints congregations, 42% of Assemblies of God churches, 29% of Roman Catholic and Orthodox congregations, 39% of evangelical Protestant congregations, and 27% of old-line Protestants.

David Roozen, former director of Hartford Institute for Religion Research and co-coordinator of the Faith Communities Today study, credits the growth to several factors. “The immigration of Muslims who are professional people is significant,” he said. According to the Hartford professor, there is also a growing self-consciousness and self-confidence among American Muslims. The events since 9/11 indicate that American Muslims are eager to be full participants in the mainstream of US cultural and political life, he said.

Roozen noted that there has been considerable debate about the number of Muslims in the United States. “There are credible arguments for both the high and the low ends of the projected Muslim population,” he said. “We simply don’t know how many Muslims there are, but the FACT data certainly suggest that Islam is one of the fastest growing religious groups in the United States.”

Not only are there more Muslim members in mosques, but there are also many more new mosques in the US than a decade ago. According to the FACT survey, the total number of mosques in the United States increased 42% between 1990 and 2000. This is a considerable rate of new growth, especially compared with a 12% average increase for the study’s evangelical Protestant denominations and a 2% average increase among old-line Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox groups.

Dr. Jane I. Smith, former co-director of the Duncan Black MacDonald Center for the Study of Islam, pointed out that in the 1980s and 90s, mosques and Islamic centers were built with generous contributions from abroad. Now, she says, most are being constructed by American Muslims. “There now are many affluent Muslims in America—individuals with organizational skills and with sufficient financial means to build the mosques and Islamic centers that are now common all across our nation,” Roozen noted.

According to retired Professor Ihsan Bagby, these masjids generally include several national and ethnic groups. “Most US masjids are intercultural and include Muslims from Asia and Africa and Europe as well as from several Arab countries.” Dr. Bagby states that a racial or ethnic focus is contrary to Qur’anic teaching. He reports that 93% of all US mosques are attended by more than one ethnic group.

“As a matter of fact,” Bagby says, “only about 27% of US mosques emphasize an ethnic focus, and most of these are located in African American neighborhoods.” By contrast, among Christians, 64% of Latino congregations in the United States and 50% of African American congregations place a high priority on preserving their racial, ethnic, or national heritage.

Preserving religious culture is deemed more important, with 69% of mosques providing prayer services five times daily year-round and 70% providing weekend religious classes.